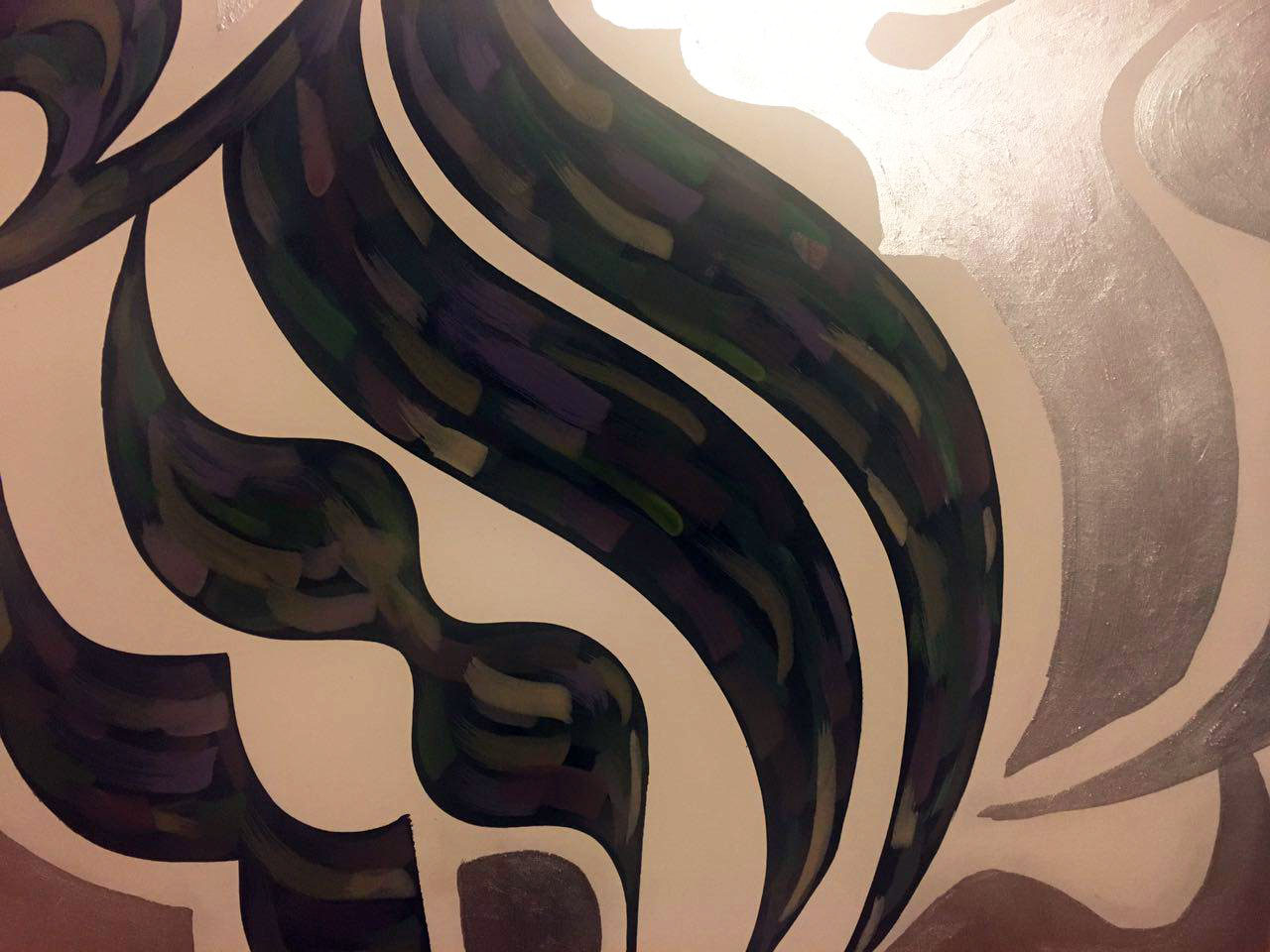

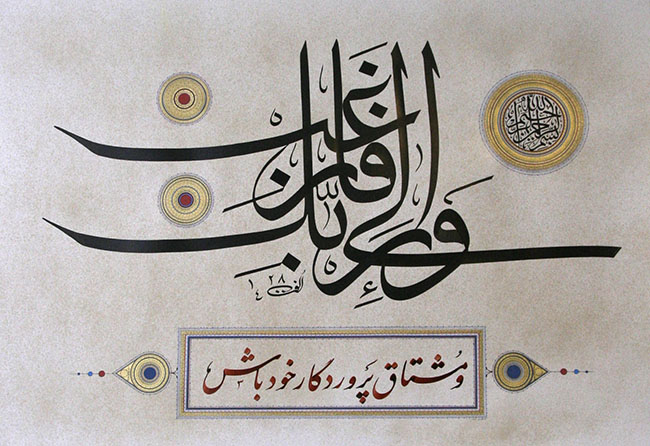

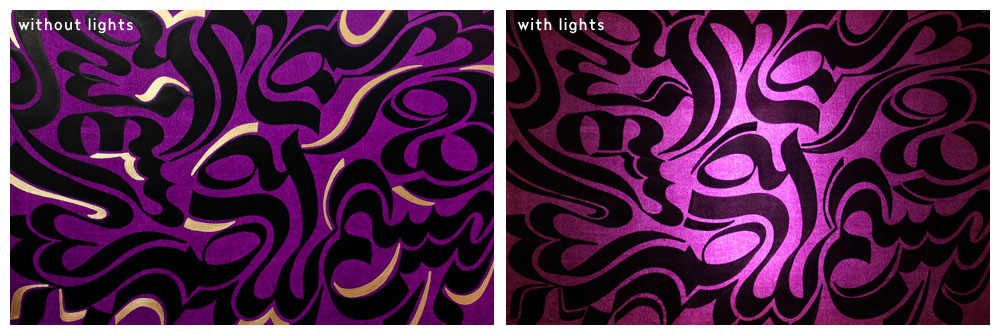

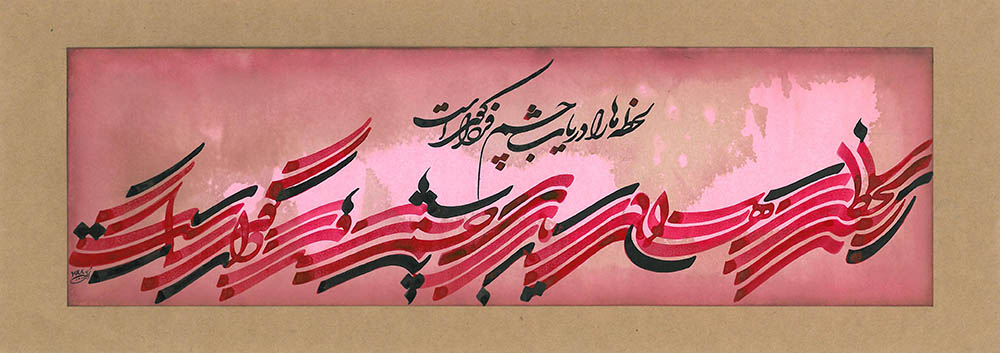

black and Wight calligraphy

In the short film “In-Out (Antropofagia)” (“In-Out (Cannibalism)”), from 1973, we see close-up shots of different mouths, men’s and women’s, as they babble and swallow and regurgitate eggs or multicolored strings. Another film, “Y” (1974), features the artist blindfolded, her mouth wide open and screaming without end. The mouth, in these works and in similarly intense photographic series, expresses the political limitations of the era, and perhaps too her constraints as an immigrant and a woman. It also serves to recall Oswald de Andrade’s “Cannibal Manifesto” of 1928, the most enduring text in modern Brazilian art history, which advocated for an art that absorbed European, African and indigenous Brazilian influences, without regard to their relative status in western capitals.

While Ms. Maiolino was creating these harrowing works, she also spent the 1970s crafting wily collages, whose papers were not laid onto a single support but mounted in boxes, and therefore perceptible in three dimensions. These “Desenhos Objetos” (“Design Objects”), making use of folded papers that she punctured and perforated, look back to the geometric abstraction of postwar Brazil, though there’s an ire, too, in their gashed edges and hidden interiors.

Credit

Anna Maria Maiolino

Those paper works offer some essential preparation for Ms. Maiolino’s recent art, including her cunning late drawings and wall-mounted works of gouged plaster, which play similar tricks with inside and outside. Above all, they set the stage for a dramatic new installation making use of one of her favorite mediums, unfired clay. For “Estão na Mesa” (“They Are on the Table”), created especially for this exhibition, hundreds of clay cylinders, crescents and braids lie on a simple wood table, as if waiting for the kiln. Piles of vermiform clay are heaped on the floor.

The brown clay objects recall ancient weights and measures, extruded taffy, piles of pasta, or the knot-shaped classic Italian cookies known as tarralucci; excrement, too, unavoidably. Again, the metaphor of alimentation exceeds easy decoding — yet these late clay and plaster works are engaged, like her earlier work, with the discrepancies between individual and social life. They are personal and yet systematic, fragile and yet nourishing. And they are masterworks.

This retrospective has been organized by Helen Molesworth, who joined MOCA as chief curator in 2014, and Bryan Barcena, a research assistant for Latin American art at the museum. I hope it gets the attention it deserves, not only within the giant PST, but within a downtown Los Angeles art scene where MOCA, one of the country’s most important museums, has lately been in the shadow of some ostentatious new arrivals.

The galleries were quiet when I visited this vital retrospective, while hundreds of chancers baked on Grand Avenue hoping to get into the Broad, MOCA’s new neighbor across the street. Hauser & Wirth, the mega-gallery down the road (which represents Ms. Maiolino), had numerous visitors in its art spaces, and far more in its in-house restaurant. They would do well to pop into MOCA too. Ms. Maiolino knows there are other, more lasting kinds of nourishment.

black and Wight calligraphy | calligraphy | Calligraphy | Modern Calligraphy| نقاشیخط | کالیگرافی | 09121958036 | ebrahimolfat.com