[ad_1]

Credit

Philip Greenberg for The New York Times

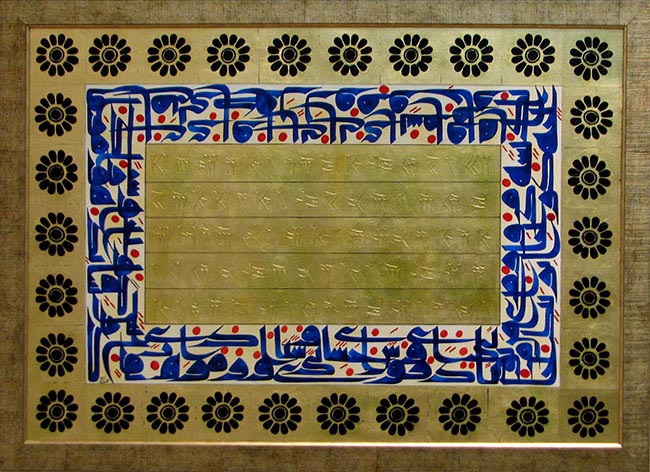

In the winter of 1965, the Museum of Modern Art opened “The Responsive Eye,” the landmark show that introduced Op Art and related trends to the general public. It was the museum’s most popular exhibition to that date. Now, 51 years later, “The Illusive Eye: An International Inquiry on Kinetic and Op Art” at El Museo del Barrio looks back on that show and finds it wanting.

On the face of it, “The Illusive Eye” is a more modest affair than its predecessor, but it’s animated by philosophical ambitions that are exciting to ponder. Presenting 65 works from the 1950s through the 1970s, it’s partly intended to reveal what the MoMA show overlooked: the extent to which Latin American artists contributed to the Op and kinetic art movements. (MoMA had featured mostly Americans, British and European artists, including Frank Stella, Ellsworth Kelly, Bridget Riley and Victor Vasarely.)

Of the 53 artists in “The Illusive Eye,” 37 are or were from one of eight South American countries or Puerto Rico. Some, like Gego (Gertrude Goldschmidt), Hélio Oiticica and Lygia Pape, are fairly well known today. But many of the show’s most optically arresting works are by artists who might be unfamiliar to North American viewers. Among those are Ernesto Briel’s small ink drawing “Nebulosa” (1969), a circular composition that seems to pulse and spin; paintings by Eduardo Mac Entyre from the mid-60s, consisting of gossamer nets of fine lines that look as if designed using a Spirograph; and Julio Le Parc’s “Continuel Lumière” (1966-68), a curtain of suspended, shiny metal squares reflecting light in all directions. One of the most entrancing sculptures is a sort of tall cabinet by Martha Boto called “Graphisme Kaleidoscopique” (1965). It has a curved, mirrored interior within which revolving mirrored discs produce mesmerizing, woozy reflections.

Credit

Philip Greenberg for The New York Times

There are also paintings by some artists who were in “The Responsive Eye,” including pieces by Josef Albers, Richard Anuszkiewicz, Mr. Stella and Mr. Vasarely.

As organized by Jorge Daniel Veneciano, El Museo’s executive director, the show aims beyond demographics, and that’s what gives it an intriguing conceptual urgency. Dissenting from previous ways of seeing and interpreting Op and kinetic art, it aspires to cast these genres in a new and different light. A museum news release makes this suggestive characterization by Mr. Veneciano: “‘The Illusive Eye’ is about illusions — those we see and feel when we look at Op and kinetic art and those experienced by the curators and art historians of these movements.” Some custodians of art, he is saying, have been blinded by their own illusions to much of what Op and kinetic art have to offer.

Some background is in order. In today’s art, the devices of Op and kinetic art are ubiquitous. Ms. Riley, an originator of Op, is now one of the world’s most esteemed contemporary painters. Her “Straight Curve” (1963), a black-and-white gridded painting that seems to bulge and torque, is among this show’s best pieces. Exhibitions featuring elements that move and light up also are common these days. But in the ’60s, some critics — notably the archformalist Clement Greenberg — saw these genres as gimmicky, merely entertaining novelties.

Advocates defended Op and kinetic art along two fronts. One tactic was to give Op an art-historical pedigree dating at least as far back as the Impressionists, who focused on perceptual experience. As vanguard painting tended increasingly toward abstraction during the first half of the 20th century, Op Art could be seen as a culmination of a drive to expunge imagery, symbolism and personal expression from painting in the interest of formal purity.

The other justification was scientific. To experience an Op painting’s illusions — the apparent vibration, motion and three-dimensionality of a picture that was actually flat and static — would be to become conscious of the often deceiving roles played by our biologically given faculties of perception.

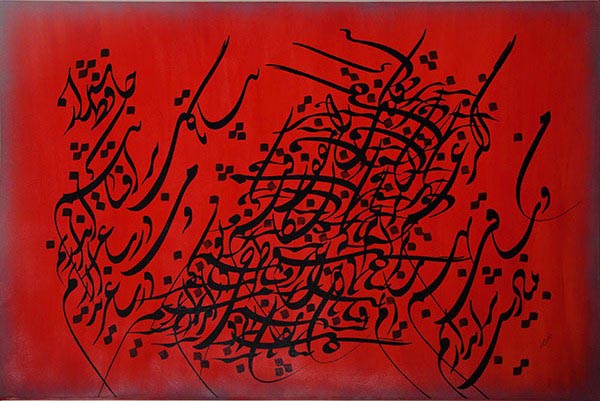

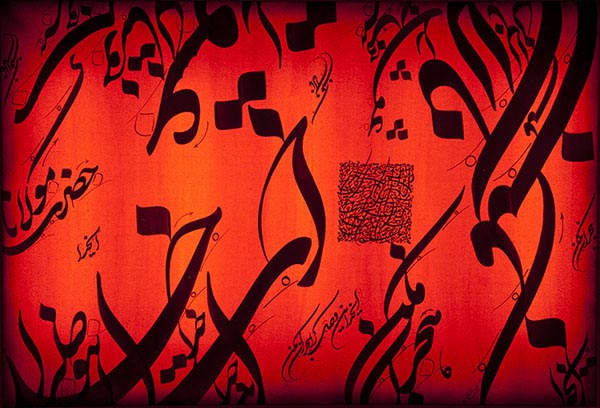

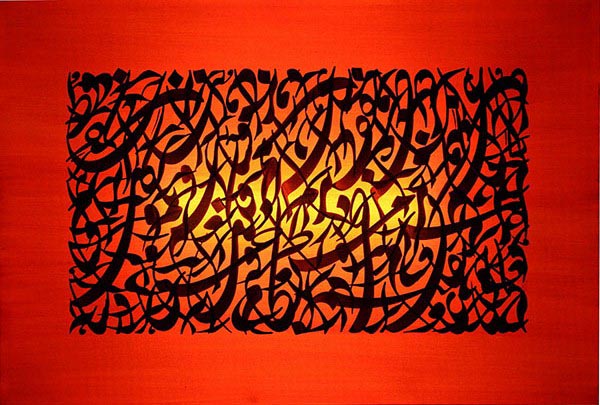

The El Museo’s show proposes a far more expansive approach, one that considers poetic, mystical and religious precedents, associations and meanings. As the exhibition brochure’s effusive text has it, “In ‘The Illusive Eye’ we find labyrinths and mirrors, hallucinatory machines in dervish gyration, hypnotic oculi (eyelike portals) and rapturous mandalas (geometric roselike symbols).” Further on it finds in Op “heaven and hell, the loss and redemption of self.” Referring to a part of the exhibition called “Mandalas and Dervishes,” the brochure invokes the whirling dances of Sufi adepts: “Gyrating works in this group invite hypnotic or psychedelic imbalance — mystical experiences by other means.”

Mr. Veneciano wants to overturn what he sees as the secularist prejudices of academic art historians and unimaginative museum curators. In this he’s in league with untold numbers of 20th- and 21st-century artists who have found creative inspiration in programs like Neoplatonism, Theosophy, the kabbalah, Rosicrucianism and astrology. That’s not to mention consciousness-altering substances.

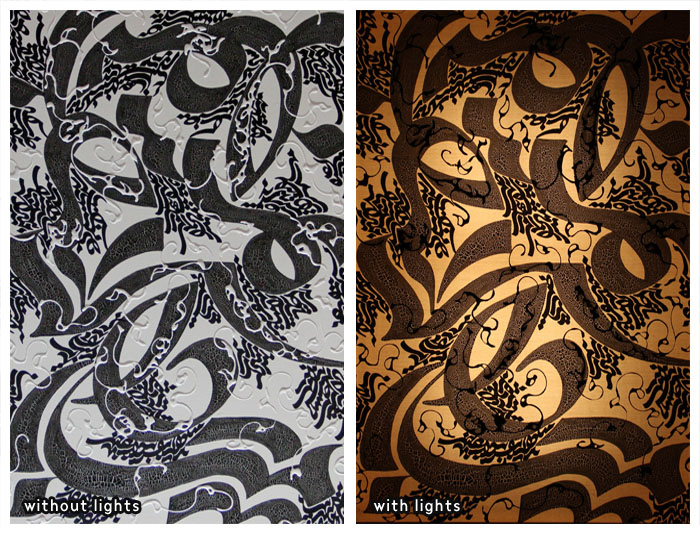

To engage fully with art on Mr. Veneciano’s terms presumably would involve more than just looking and judging. It would be a kind of meditative, soulful surrender to the totality of art’s psychic effects. Consider, for example, a graphic image installed on the floor in a dark-walled room of its own, a replication of a piece from 1966 by Marina Apollonio, of Italy, called “Spazio ad Attivazione Cinetica 6B.” A black-and-white composition of off-center circles within circles, it’s altogether 15 feet in diameter. As you walk around and on it, the circles seem to swerve and spiral to dizzying effect. To take a few turns is amusing. But what if you continued to circulate for a much more extended time, like a whirling Sufi? Might you find yourself drawing closer to God, or the functional equivalent?

Ms. Apollonio’s piece inadvertently points up a problem with the rest of the exhibition: its conventional installation in an antiseptic, white-walled environment. This standard presentation promotes the clinical, objectifying, secular way of seeing that the show’s brochure and interpretive text labels argue against. What would an exhibition that brought out all that Mr. Veneciano finds in Op and kinetic art look like? That would be a hard but possibly tremendously fruitful question to answer.

[ad_2]

Source link