[ad_1]

Credit

Swann Auction Galleries

When slaves fled American and British farms and townhouses, their owners often placed detailed newspaper ads offering rewards to anyone who returned the fugitives. The written notices described the runaway slaves’ mannerisms, clothes, hairstyles, skin markings, teeth and skills, as well as information about plantations that the escapees might have tried to reach, hoping to reunite with family members or less cruel past owners.

New databases are enabling historians and descendants of slaves to piece together family trees and identify patterns in the lives of runaways. These searchable listings indicate how often slaves managed to leave with their children, how some were able to pass for white and how many recaptured slaves kept trying to escape.

Among the new website projects are Runaway Slaves in Britain, set up by the University of Glasgow, and Freedom on the Move, based at Cornell University and covering American newspapers.

The content can be harrowing.

The scars mentioned in the brief ads make clear how often the men, women and children in captivity were whipped, beaten and shot, were forced to wear metal collars and had their faces branded. Some advertisers offered bounties for the escapees’ corpses or decapitated heads.

Joshua Rothman, a history professor at the University of Alabama who is working on Freedom on the Move, said that for researchers in the field, there are moments when “you really just are left hollowed out.”

Regional databases have focused on ads for runaway slaves from Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, Louisiana and Mississippi, among other places. Freedom on the Move and Runaway Slaves in Britain will further shed light on the scale of slave resistance and resourcefulness.

The total number of these ads printed in America most likely surpasses 200,000, representing a small fraction of the actual fugitive population. Only those who were still believed to be on the run for at least a week or so would have given the owners enough time to have the ads published.

Edward E. Baptist, a history professor at Cornell who oversees Freedom on the Move, said many fugitives returned after a few days, such as women who left behind children and older relatives needing care. “People in that situation were not typically advertised for,” he said.

Mary Niall Mitchell, an associate professor at the University of New Orleans who is also working on Freedom on the Move, said escaped slaves who ended up in New Orleans could sometimes mingle with the city’s free blacks and find work. But newspapers would have kept white citizens informed about what the fugitives looked like, so blacks on the streets would have been scrutinized. “It’s a whole web of gossip and surveillance,” Dr. Mitchell said.

Meaghan E. H. Siekman, a senior researcher at the New England Historic Genealogical Society in Boston, said the owners wrote ads “describing people like a jacket that they’d lost.” By noting the slaves’ skills — ranging from carpentry to violin playing — the ads made it harder for them to find jobs in free states, she said. Revealing their expertise left them vulnerable to being identified and recaptured.

The genealogical society is expanding its databases related to African-American family trees, making it possible to connect names to ads for runaways. The ad databases can also be scanned for names that appear in slave owners’ correspondence, receipts for slave sales, memoirs by escapees and government files for blacks who became Union soldiers.

Courthouse records also survive for fugitives who fought legal battles to stay free. Simon P. Newman, a professor at the University of Glasgow who is working on the Runaway Slaves in Britain database, has studied the case of Jamie Montgomery, a teenage slave who was taken from Virginia to Scotland in the 1750s. He trained as a carpenter, increasing his value, and his owner then planned to sell him back to American farmers. Mr. Montgomery fled when he was about to be shipped to Virginia and began legal proceedings to be emancipated in Scotland. He died in government custody before a court ruled on his case.

Dr. Newman said that slavery’s pervasiveness in England and Scotland, in villages and urban centers, has long been little known. Thousands of ads for fugitives were published there. “This whole forgotten world is opening up to us,” he said.

Credit

Swann Auction Galleries

More information about runaways in New England is coming to light, too. Michelle Arnosky Sherburne, author of a new book, “Slavery & the Underground Railroad in New Hampshire,” has uncovered hundreds of ads published in Vermont and New Hampshire, as well as anecdotes about white residents helping runaway slaves. In 1862, a runaway arrived on a rainy spring night at James Wood’s farm in Lebanon, N.H. “I fixed him a bed in wool room,” Mr. Wood noted in his diary.

Historic Hudson Valley, an educational and preservation organization in Pocantico Hills, N.Y., has introduced a school curriculum module based on runaway slave ads, and it is creating a database about slaves in Northern colonies. On Sunday the Staten Island Museum is hosting a lecture about Revolutionary War soldiers in the region, including Colonel Tye, a fugitive slave from New Jersey who fought for the British.

Stephen Berry, a professor at the University of Georgia, is posting reports from county coroners in a database called CSI: Dixie, which shows how often slaves were murdered while trying to escape.

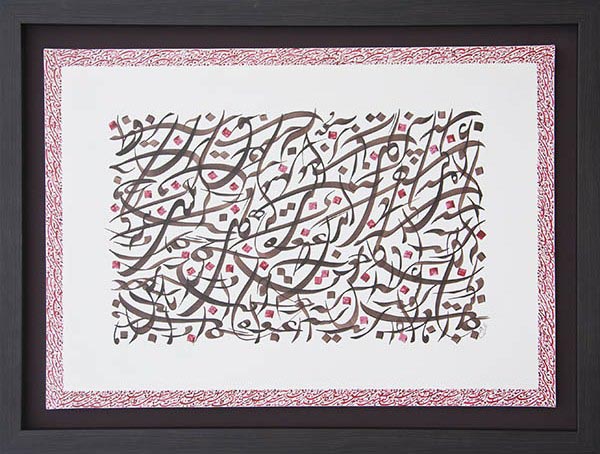

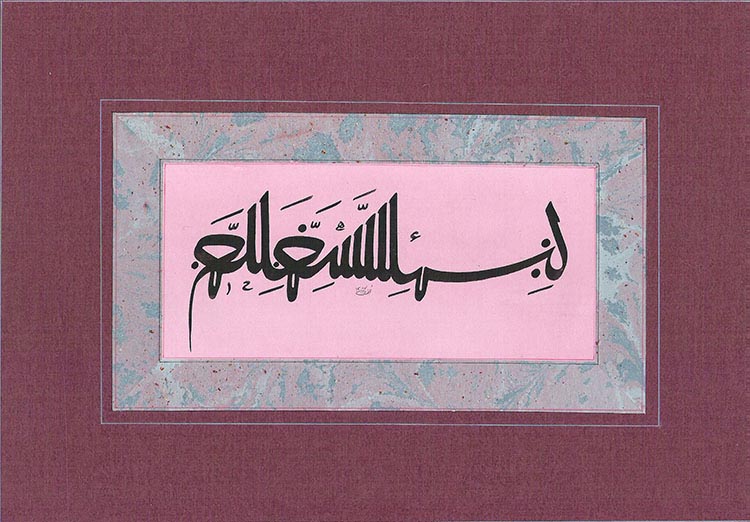

Related artifacts have been surfacing in museums and at auctions.

At an annual sale last year of African Americana at Swann Auction Galleries in Manhattan, a portrait of a runaway slave named Elisa Greenwell from a Maryland tobacco plantation was sold for $37,500 to the National Museum of African American History and Culture, which will display documentation of escaped slaves when it opens in September. On March 31, Swann will offer ads for fugitives (estimated at a few thousand dollars each). A broadside from the 1850s promised $100 to anyone who returned a young slave named Mehlon Hopewell to a Maryland plantation owned by the prominent Boteler family. The escapee rode away on a horse taken from a local physician, and left it behind once he reached some nearby mountains. A few years after the runaway’s daring maneuver, John Brown organized his failed rebellion not far from the Botelers’ lands, and then Union and Confederate soldiers ended up slaughtering one another there.

[ad_2]

Source link